It’s been half a year since the last post about Ashtanga (eight limbed) yoga, and in that time I’ve developed a regular meditation practise. Yet, whilst I can no longer call myself a complete beginner, I still stumble over the basics.

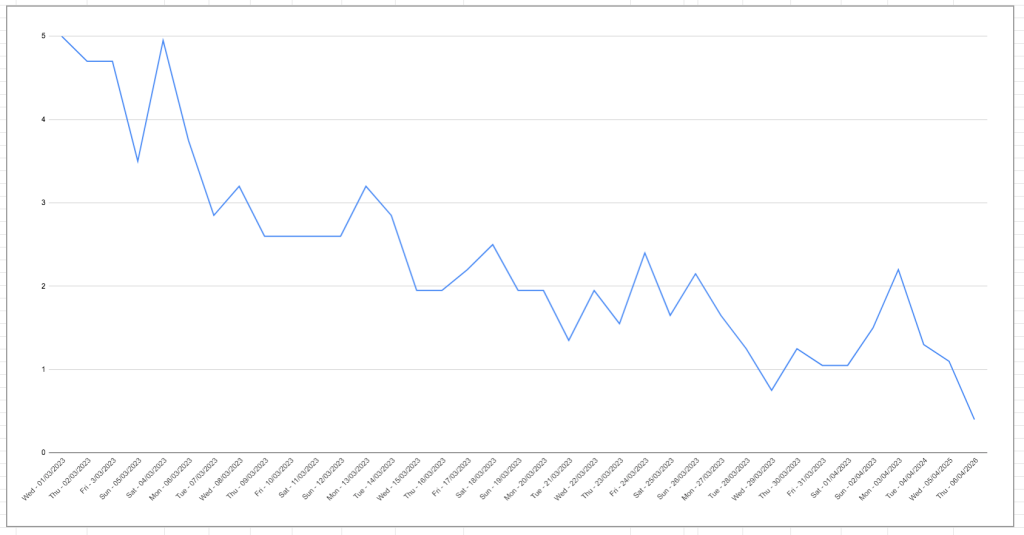

Something to challenge is the idea that though Ashtanga yoga defines a stepped progression, that progress is linear. Whilst it’s easy to conceive of moving up a ladder one rung at a time until you find yourself floating on a cloud with yogic superpowers, it’s unlikely. Instead it’s likely that one will halt at a rung, perhaps too distracted to contemplate the next step.

Nevertheless, the past few years have seen development which bodes well for what’s to come, and in sharing them here I hope there are things that will resonate and support other yoga journeys.

Meditation refers to a family of self-regulation practices that focus on training attention and awareness in order to bring mental processes under greater voluntary control and thereby foster general mental well-being and development and/or specific capacities such as calm, clarity, and concentration.

Walsh and Shapiro 1976

Perhaps the first thing to say is that it gets easier.

Though whilst it’s natural to think application and hard work deliver improvement, inevitably there are times when progress stops or even slips backwards, when its better to call it a day and look forward to tomorrow. But just as with a weight chart, the overall trend is more important than the daily peaks and troughs. Sometimes meditation doesn’t go well, and acknowledging that’s only to be expected is helpful, perhaps even necessary.

It’s not only reassuring to realise and accept that just like riding a bike there are wobbles and “offs”; acceptance is also required to let things such as a buzzing fly, or swallowing (increased salivation is common during meditation), pass without disruption. Recognising that acceptance is necessary has been a revelation.

In yoga the gateway to meditation is the breath (Pranayama). The fourth limb of the ashtanga tree, Pranayama and Pratyahara (introspection) mark the boundary between yoga’s physical and metaphysical aspects: good behaviour, observance, posture and breathing set one up for introspection, focus, meditation and unity. The body needs to be conditioned to sit peacefully and attentively, the mind stilled and steadied in order to explore consciousness.

With Pranayama, the breath is the pulse: energy and light flow in with the air, and stillness and peace descend as it flows out. Though it shouldn’t require effort, gentle realignment is needed when attention is captured by a passing thought. I find it easier to remain at the bottom of the breath with lungs deflated as, unlike when they’re full, nothing’s required to counteract the pressure of an expanded rib cage. It’s a good space to hold, so much so that I sometimes feel like staying there forever. And that’s another thing, one’s sense of time passing distorts.

During meditation. various feeling and thoughts may arise.If you don’t practise mindfulness of the breath, these thoughts will soon lure you away from mindfulness. But the breath isn’t simply a means by which to chase away such thoughts and feeling. Breath remains the vehicle to unite body and mind and to open the gate to wisdom.

The Miracle of Mindfulness – Thich Nhat Hahn

One can wonder am I doing it right, am I meditating?, when the definition lies partly within. Experience can always be extended and deepened and respiration, pulse and brainwaves measured, but both objectively and subjectively meditation seems quite hard to define and know.

Without distracting thoughts the mind has more capacity to attend and perceive. When meditating, sensation is enhanced not diminished which leads to a more acute awareness of where the body meets the world. In my practise, that’s most obviously the feeling of the floor beneath, the air entering my nose, the slight constriction of my throat and activation of “anchors”: particular sensations that, through repetition, become associated with, and so can trigger a relaxed state e.g. mudras.

Just as unrolling the yoga mat and standing tall helps to prepare for asanas, so now a few breaths, the connection of thumb and middle finger, and turning inwards, initiate a meditative response: stillness descends, the breath slows and settles, and attention turns from thought to sensation. Going deeper finds an immersion in the gaps between in-breath and out-breath. Though it’s hard to say if this is actually meditating, or what’s needed before it does, the state I find is compelling and qualitatively different from everyday consciousness.

I recently joined a mysore, ashtanga yoga class which has highlighted where, after seven years of practise, my technique could be improved (everywhere), and how some of the asanas in even the primary series will remain aspirational for a while yet. That’s OK too, remedial work, learning about what we’re aiming for and what it takes to get there, are all relevant.

Something that’s also made me think recently was pilfering a marker pen from work. Though petty, it doesn’t accord with Asteya the third Yama of yoga’s first limb. Time served is no excuse for complacency and the journey is just as important as the destination.

Empty your mind of all thoughts.

Let your heart be at peace.Tao Te Ching

With attention focused upon the here and now, and the chatter of the monkey mind quietened, sensation is more acute and awareness of one’s surroundings more vivid. Instead of being removed a feeling of being more integrated. This has been surprising, and there’s more.

Where we practise there’s sometimes the sound of birdsong and smashing of bottles at the bottle bank next door. Both could be taken as distractions, but instead I’ve come to accept them as part of the meditation experience. Perhaps that suggests a lightness of touch is required, to fully experience what it is to be here and now. The moment is as fleeting as clouds passing across the sky.

Somewhat counter intuitively meditation doesn’t seem to be about withdrawing from the world, if anything quite the opposite. It can be easier to meditate in company and to find silence in birdsong and the smashing of glass. Such paradoxes are the stuff of Zen Buddhism.

Following the breath and allowing it to permeate awareness is a beautiful thing: the connection of fingers and thumb in a shuni mudra, tongue touching the roof of the mouth, the pause between out-breath, in-breath and out-breath, all go to move one beyond sensation to profound connection.

So perhaps without the distractions of activity and the usual stream of loosely connected, but often quite random thoughts, one can better tune in to “reality”. Perhaps also through exploring the relationship between the internal and external we reveal more about what they are and the illusion that they’re different.